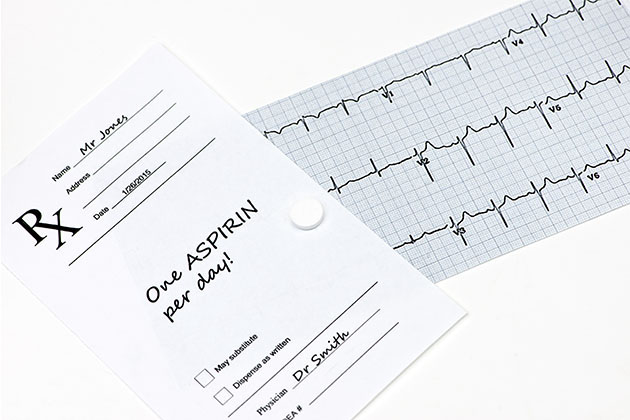

Study shows that a person’s body weight influences the effects of low-dose aspirin in preventing cardiovascular events

Daily aspirin therapy according to body weight

Studies published in The Lancet has shown in a randomized trial that effects of common medicine aspirin in preventing cardiovascular events depends heavily on the patient’s weight1,2. Thus, benefits of taking the same medication may not be similar for patients with high body weight. The study was conducted with people having body weight between 50 and 69 kilograms (kgs) (around 11,8000 patients). They consumed a low dose of aspirin (75 to 100 mg) and it was seen that around 23 percent has lower risk of heart attack, stroke or another cardiovascular event. However, patients having weight more than 70 kgs or even who were lighter than 50 kgs did not seem to have received similar benefits of low dose aspirin. Low dose of aspirin was actually harmful for patients who weighed more than 70 kgs and fatal for patients less than 50 kgs. And, giving these patients a higher dose though beneficial would be problematic as the next high dose of aspirin was a full dose of 325 mg which is known to cause adverse bleeding in some patients. Though this risk of bleeding went away for patients weighing more than 90kg. However, it is still to be considered about how much higher dose can be given because many individuals fall in 70 kg+ category and thus benefits and risks have to be analysed together.

Therefore, the importance of body weight is vital when discussing efficacy of aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events and also cancer. The approach of ‘one size fits all’ needs to be dismissed and a more tailored and personalized dosing strategy needs to be adopted. Though the exact recommended dose with people with higher body weight (more than 70 kgs) is still to be researched upon. The authors do suggest that a full-dose aspirin should be consumed daily by people who weigh more than 69 kgs or are heavy smokers or suffer from an untreated diabetic condition. The higher dose would be protective towards at-risk patient who are more likely to suffer from undesired blood clot formation. Interestingly, no differences between stroke rates amongst genders were detectable when only the body weight was the sole criteria. A low-dose aspirin is not effective in 80 percent men and around 50 percent women who weigh at least 70 kgs thereby challenging the current common practise of prescribing low dose aspirin to all patients in the 50 to 69 age group.

The study suggests that best benefit of aspirin for long-term prevention of cardiovascular events should be focussed on under dosing in big individuals while overdosing in small. One of the direct implications of this study is to dissuade widespread use of high dose of aspirin (325 mg) in low weight people (less than 70 kgs) as it is seen that lower doses are effective enough minus any hazards of excess dosing. And excessive dosage could be even fatal. More research needs to be carried out to these validate findings. But clearly these results have the potential to affect public health systems by persuading discussion of weight-adjusted dosage of aspirin in routine clinical care. Also, comparisons of aspirin with other antiplatelet or antithrombotic dosages be also based upon body size and weight. It is clear that the most ideal dose of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular diseases/events is dependent on body weight – i.e. body mass and height rather than BMI (Body Mass Index). This study also puts forward the idea of precision medicine i.e. providing a personalised therapy to each patient.

***

{You may read the original research paper by clicking the DOI link given below in the list of cited source(s)}

Source(s)

1. Rothwell PM et al. 2018. Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. The Lancet. 392(10145).

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31133-4

2. Theken KN and Grosser T 2018. Weight-adjusted aspirin for cardiovascular prevention. The Lancet.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31307-2

***